Since the revolution in Libya, Gaddafi loyalists and members of his tribe have been marginalised. Some have chosen exile and wonder if they can ever return home.

On the last night of Ramadan six years ago, NATO bombed two homes in the town of Bani Walid, one of the last strongholds of Muammar Gaddafi’s regime. Salem Mohammad, who was sitting in the garden, was the lone survivor. The others – a family of five including a nine-year-old girl – were pronounced dead the following morning, 30 August, 2011. They had sheltered Salem and his brother Khaled after they were uprooted by the war, and were some of their closest friends.

After the blast, Khaled Mohammad sprinted towards the rubble and found his brother Salem unconscious and bleeding, shrapnel protruding from his back and legs. He ran to an open minibus parked nearby and pulled out the back seats, carrying Salem into it with the help of a friend.

Militias have taken justice in their own hands by killing [Gaddafi supporters].

“We were speeding to the nearest hospital while I held my brother in the back seat,” says Khaled, a native of Sirte and a member of al-Qadhadhfa, the same tribe as Libya’s slain dictator. “The hospital we reached had few supplies. Doctors told us that we had to take my brother to Zawiya, but that city was controlled by anti-government forces.”

Instead of driving to Zawiya, Khaled bribed an ambulance driver to take them to Tunisia. After Salem received life-saving treatment they settled there, remaining for a year and a half. Khaled is now in Egypt, journeying to Cairo with his brother in early 2013. And while Salem returned to eastern Libya last year, Khaled can’t imagine returning unless militias are disarmed and the rule of law is restored.

It’s tough to blame him. Since the revolution, the country’s main rival militias have supported one of three governments competing for power – two in Tripoli, the country’s capital, and one in the far east city of Tobruk. But tribes who supported Gaddafi against the popular uprising are neglected by all three in power-sharing agreements. Some members of al-Qadhadhfa have chosen to live in exile like Khaled, while others have made fraught and even perilous decisions for the sake of survival or retribution.

Revenge

Mass protests against Gaddafi’s rule began in February 2011, but it was only after months of civil war that his regime was toppled. Some of the war’s bloodiest fighting occurred when regime forces besieged Misrata for three months. When Gaddafi and his forces retreated to their final hold-out of Sirte, home to many from the Qadhadhfa tribe, fighters from Misrata descended on the city to seek retribution, memories of the siege earlier that year still fresh.

After his troops lost control of Sirte, Gaddafi was summarily executed on 20 October. The very next day, one of the bloodiest acts of revenge took place when at least 53 regime captives – possibly as many as 66 – were executed at a hotel in Sirte, documented by Human Rights Watch (HRW).

The following year, Gaddafi loyalists were excluded from politics. The General National Congress, the ruling body at the time, passed a political isolation law that effectively barred anyone affiliated with the previous regime from holding public office. Rights groups criticised the move for polarising rather than reconciling divisions.

Hardly any Libyans understood the law or wanted it to pass, says Noor Al-Huda Gleasa, co-founder of I’m Tawfik, a human rights group named after Tawfik Bensaud, a youth activist assassinated by militants in Benghazi in 2014. Parliamentarians didn’t have a choice but to support the law, she recalls – militias threatened to kill them if they didn’t vote for it.

“It’s not fair to bar people who worked for the former regime from participating in government,” she tells zenith. “[The law] was forced on the people. We didn’t vote for it.”

I’ll only participate in future elections if Saif al-Islam is an option in the ballot box.

The marginalisation of Gaddafi loyalists fuelled their resentment. Meanwhile, Libya was becoming increasingly lawless and chaotic. The self-declared ‘Islamic State’ group (IS) sought to take advantage of the ensuing turmoil, establishing a presence within the country by the end of 2014, and in Sirte by early 2015. Many Qadhadfha men joined the jihadist group, also known in Arabic as Daesh.

Moad, a human rights activist from Tripoli who declines to give his last name for fear of reprisal, suggests that it was the collective grievances of the tribe that inspired large numbers of its young men to join the ranks of the jihadist group, rather than religious or ideological aims. “Many Gaddafi loyalists didn’t join IS because they believed in what the group had to offer them. They joined to settle scores with militias from Misrata.”

But not even IS could help in their quest for payback. By December 2016, the group had been defeated in Sirte by forces loyal to the UN-backed Government of National Accord (GNA). Militias from Misrata led the charge again.

All the while, Gaddafi loyalists across the country were subject to reprisals. In June 2016, 12 figures from the old regime were murdered after being released from a prison in Tripoli. “Militias have taken justice in their own hands by killing [Gaddafi supporters],” says Gleasa. “But it’s not their place to enforce justice.”

A convenient alliance

Other players in Libya are starting to make concessions to figures from Gaddafi’s regime, ostensibly to win the backing of their supporters. Saif al-Islam, Gaddafi’s most prominent son, was reportedly released in June this year by a militia in western city Zintan that had captured him during the final days of the revolution. However the circumstances surrounding Saif remain unclear (within Libya there are even rumours of his death). In June that militia said Saif was released in line with the general amnesty that the Tobruk government passed in 2015, which stated that anyone who murdered, tortured, or raped others because of their race or ethnicity wouldn’t be pardoned, yet those who ordered the killing of protestors could be freed.

Saif is a polarising figure in Libya. There were once widespread hopes that he could be a reformer for their troubled country, but those dreams were dashed at the beginning of the revolution when he sided with his father as he brutally repressed protestors. The International Criminal Court has requested that he be handed over and tried for war crimes. Nevertheless, Saif’s tribe and others have renewed hope after hearing of his release.

One way for Saif to become a major player is to align with Field Marshal Khalifa Haftar’s self-declared Libyan National Army (LNA), which backs the Tobruk government. Haftar has expressed his plan to retake Tripoli, but doesn’t have the firepower to do so unless he is aided by tribes in the south and west.

Mattia Toaldo, an expert on Libya at the European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR), tells zenith that Saif has two options. “The choice for Saif and the pro-Gaddafi camp, which is quite divided, is whether to become a third force in Libya or to become Haftar’s fifth column in the south and west,” he explains.

The decision isn’t easy, since many Gaddafi loyalists consider Haftar a traitor. The history is revealing. In 1987, Haftar commanded the Libyan national army in battle against Chad, until he was captured along with hundreds of his men. Gaddafi – the self-proclaimed ‘brother leader’ – publicly disavowed them. Seeking revenge, Haftar joined the CIA-backed National Front for the Salvation of Libya while still in prison. The group, based in Chad, plotted several coups against Gaddafi’s regime. All failed.

Other observers, added Toaldo, say that Abdullah Senussi and Abu Zayd Umar Dorda – two former and brutal chief intelligence officers from Gaddafi’s regime – wield considerable influence. Yet there isn’t much they can do since they are both reportedly in prison (there are also reports that Senussi has been released).

Khaled Mohammad says he’s ready to move on from the past for the sake of an alliance, but true reconciliation appears unlikely any time soon. War criminals have been pardoned while human rights activists and former security officers have been murdered across the country. Khaled has also said that he’s reluctant to trust or befriend anybody who supported the revolution.

Despite doubts about whether Saif is even alive – he hasn’t released a statement since his reported release, and no independent observer has seen him since 2014 – Khaled is nonetheless hopeful. Like many Gaddafi loyalists, he considers Saif Libya’s undisputed leader.

“I’ll only participate in future elections if Saif al-Islam is an option in the ballot box,” says Khaled, sitting inside an upscale café in 6 October, a suburb in Egypt’s capital. “If he’s not an option, then I don’t see the point in voting.”

Nostalgia

Khaled isn’t the only one longing for a figure from the old regime. Ahmad Yousif (not his real name), a native of the southwestern city of Sabha and a former member of the Revolutionary Committees which functioned as watchdogs for Gaddafi, tells zenith that most people in his city wish the revolution had never happened. Sabha, now notorious for its role in human trafficking, is another Qadhadhfa power centre.

People don’t miss Gaddafi, but they do miss the economic stability and security which we had compared to now.

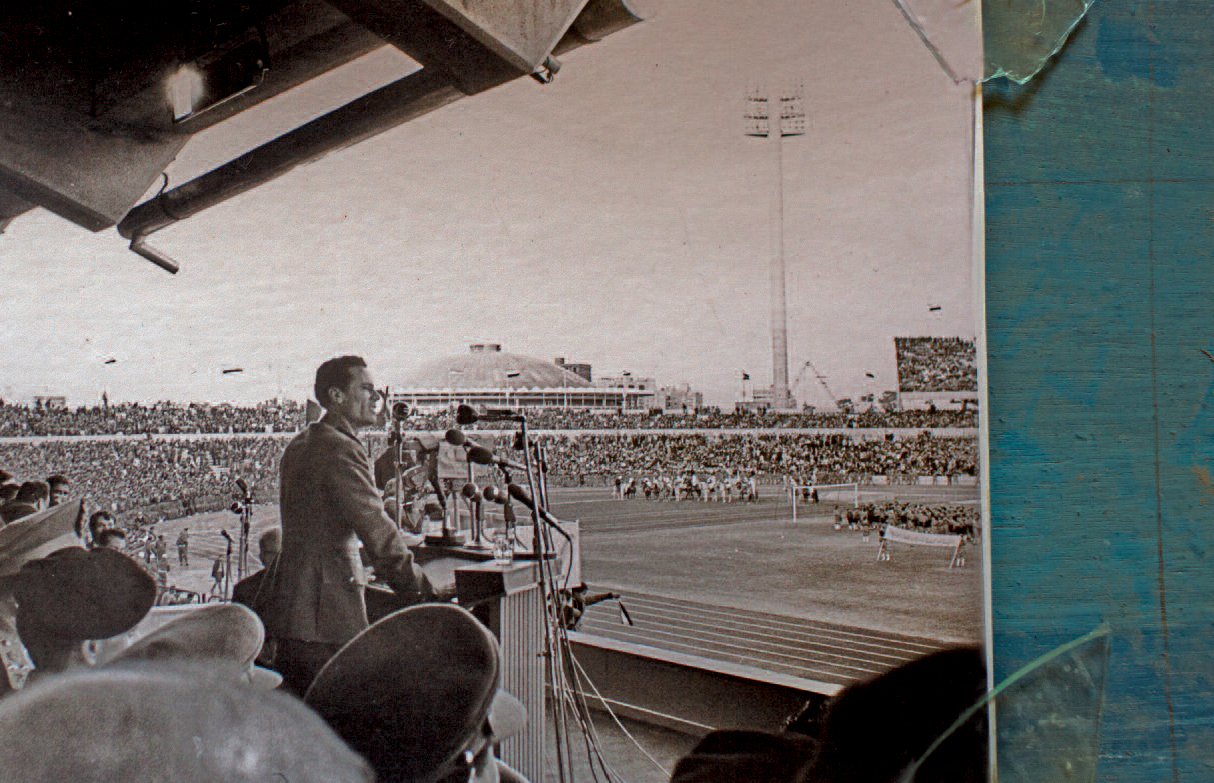

“Gaddafi did everything for us. He was our leader and our teacher,” says Yousif, speaking from Sabha, the city where a young Muammar Gaddafi attended secondary school and began his political life by organising demonstrations. “He was responsible for all internal and external affairs. There was also safety, because everyone was living in a permanent state of fear.”

Like many Libyans, today Yousif is constantly on guard for different reasons than during the regime years. The lack of a national police or military force has resulted in an extremely high murder rate. Theft is also rampant, and provisions are in short supply. In Sabha, militias frequently steal cars and property at gunpoint, while electricity cuts last for most of the day. Yousif says he works as a tradesman, but refuses to disclose what he trades.

Life in Tripoli faces similar challenges. Long power cuts, coupled with fuel and water shortages, have made basic commodities much more expensive. The mounting challenges are making people who once supported the revolution nostalgic for the Gaddafi era.

“People don’t miss Gaddafi, but they do miss the economic stability and security which we had compared to now,” says Gleasa of I’m Tawfik.

“A return to military rule isn’t going to solve our problems,” warns Yousif. “Our country has to move forwards [towards democracy], not backwards.”

For some the past offers more solace than the future. In Cairo, Khaled constantly reminisces about his old life. Before the uprising, he worked as a bank teller to support his siblings and parents, and was never professionally entrenched within the old regime despite his unwavering support for its leader.

Now that circumstances have changed, the irony is striking – those who opposed the revolution can only pray that it eventually succeeds. Without transition to an inclusive democracy and rule of law, chaos will continue unabated and Gaddafi loyalists will remain unprotected.

Khaled isn’t optimistic, which is why he recently bought his apartment in Cairo.

“I’ll only go back to Libya if the situation improves,” he says, sitting in the garden outside his compound. “I hope it does. But militias are always fighting for power. They don’t care about our country or its people.”