In Libya, African migrants run into Jihadis, xenophobia and organised crime. Encounters with passage-makers and people smugglers between the Sahara and the Mediterranean.

For four years now, Issa Hassan has stood with his taxi at a dusty intersection in the suburbs of Sabha. The derelict suburban area has come to be known as Westgate Wall, because behind the big supermarket in front of which the taxis queue up, enemy territory begins.

Only a few of 28-year-old Issa Hassan’s customers understand why a militiaman such as himself works on the side as a taxi driver. They’re used to people in uniforms earning money from all kinds of smuggling. The many dints in Hassan’s dusty Toyota testify to the conditions in the Saharan province of Fezzan. Not much news has reached the outside world from here since the 2011 Libyan revolution. And yet it is here, in the Libyan desert oases, that a serious danger for Europe may be growing.

“For five years I have been waiting for my unit, Umm al-Anarab, to be incorporated into the army so that we can take up the struggle against smugglers again. But without pay I have to drive a taxi on the side,” Issa Hassan says. Although a well-paved street leads to the Murzuk Oasis 100 kilometres away, his passengers usually ask him to take a detour on pot-holed dirt roads, far away from the Awlad Suleiman militia’s checkpoints in Sabha.

Tribal divisions

He and his passengers belong to the Toubou ethnic group, who like the Tuareg are the original inhabitants of the Sahara and are looked down on by many Arab Libyans. The few police officers and other people in uniform on the main arteries of the metropolis of 300,000 people belong to the Arab Awlad Suleiman tribe. They’re ill disposed not only toward the Toubou, but also toward the tribe of former dictator Muammar Gaddafi, even though for a long time they were among his regime’s most important allies in the desert province. Since the revolution, the Awlad Suleiman and their allies from coastal city Misrata have been calling the shots. For their part the Toubou are allied with army general Khalifa Haftar, whose troops are battling the ‘Islamic State’ (IS) and its allies in the port city of Benghazi, a thousand kilometres further east.

“The fact that we fought against Gaddafi alongside the Misratis no longer counts for anything in the battle for the oilfields,” Issa complains. As we talk, he repeatedly asks about the cost of living in Germany. “The revolution only served to hand power over from city to city and tribe to tribe. In Tripoli the Islamists ousted the anti-Islamists, in Benghazi the army took over.” He looks baffled.

In February 2011, while still a student, he protested on the streets with a handful of school friends in the name of a constitutional state, he says. In 2013, after two different parliaments and over 90 local elections, Libya seemed to be on the right path. “We revolutionaries won the battle against Gaddafi not because of our ideals, but because of our local rivalries with other cities,” he claims. “The new legal system is simple: when I come to Sabha, they shoot at me. When a member of Alwad Suleiman comes to us, we shoot at them.”

The Jihadis benefited from being on the sidelines. In the post-revolutionary confusion they first spread under the name of Ansar al-Sharia in Libya and now command respect as a North African branch of IS. Militias with close ties to IS have long maintained secret training camps in Sabha and Ubari, and one day they will set off over the Mediterranean – of that much the nearby Toubou are certain. Two kilometres from the taxi rank, in Arba district, militias run by al-Qaeda veteran Abdul Khalifa recruit members from refugees coming out of the Sahara.

Every day unseaworthy vessels set off from among the weekend houses strewn along the shore, houses inhabitants of the capital built in the suburb of Garabulli in previous years.

The Tuareg, Toubou and other tribes could rapidly solve the security problem in Fezzan province if only they would work together, an exasperated Shahafedin Barka complains as he gets out of a jeep at the taxi rank. “We know the smugglers’ two routes. With support from Tripoli and Brussels we could bring the borders back under control, as during Gaddafi’s rule.” The commander of the 1,000-man-strong Umm al-Anarab has only just returned from Ubari. A battle between barely of age Toubou and Tuareg fighters raged in the oasis for more than ten months. Neither side was able to register territorial gains. The reason a centuries-old peace between the ethnic groups was broken by the battle remains unclear, even to the protagonists.

In fact, the static war was fought primarily over the El Feel oilfield, one of the largest in Africa. Oil is actually no longer extracted in this ‘Elephant Field’, but in Libya control over such resources goes hand in hand with political influence.

Until the second civil war in spring 2014, a number of Umm al-Anarab revolutionaries earned 600 dinar a month (around 370 euros), paid irregularly by the oil ministry, by working as guards at the military camp. But then the Islamists broke ranks with the Muslim Brotherhood and seized power in Tripoli. Because the Toubou fought for General Haftar, payments from the capital failed to materialize, and they had to pay for food, munitions and replacement parts for their pick-up trucks themselves.

A surfeit of labourers - but little work

In light of the civil war and the drop in oil prices, professional people smuggling is the least dangerous job in the country for the foreseeable future. And transporting oil and petroleum to Tunisia or Algeria also entails hardly any risk, thanks to widespread corruption among border officials. In Libya a litre of petrol costs four cents, while in Tunisia and Algeria it costs up to 75 cents. Every day hundreds of trucks loaded with arms, petroleum or people cross the effectively open borders.

Under the shade of the trees lining the main street of Sabha, in the far south of Libya, thousands of dark-skinned day workers sit on their haunches waiting for work. Thanks to a surfeit of labourers, incomes have sunk to ten dinar (about three euros) a day. The price for a ride in a convoy from Niger to southern Libya has also dropped. A ride in the tray of a pick-up truck costs 150 euros. Up to a thousand people take the trip from Agadez in Niger every Monday, and from noon on Wednesday the first jeeps start to reach Libya’s oases. The traffickers advertise their services on dozens of Facebook pages, but the journeys often end up in the middle of nowhere. As soon as news of fighting in Sabha gets around, the refugees are dropped off in the desert, far from the oasis cities.

In the chaos, the Umm al-Anarab try to maintain a bit of order in the area under their control. Three years ago, with the elders in Qatrun and Murzuk, Shahafedin Barka and Issa Hassan drew up a penal code. The Toubou militia confiscate vehicles from the smugglers and fines them 4,000 dinar (around 2,500 euros), but they increasingly pick up friends and acquaintances who have decided to get in on the lucrative business, Shahafedin Barka laments.

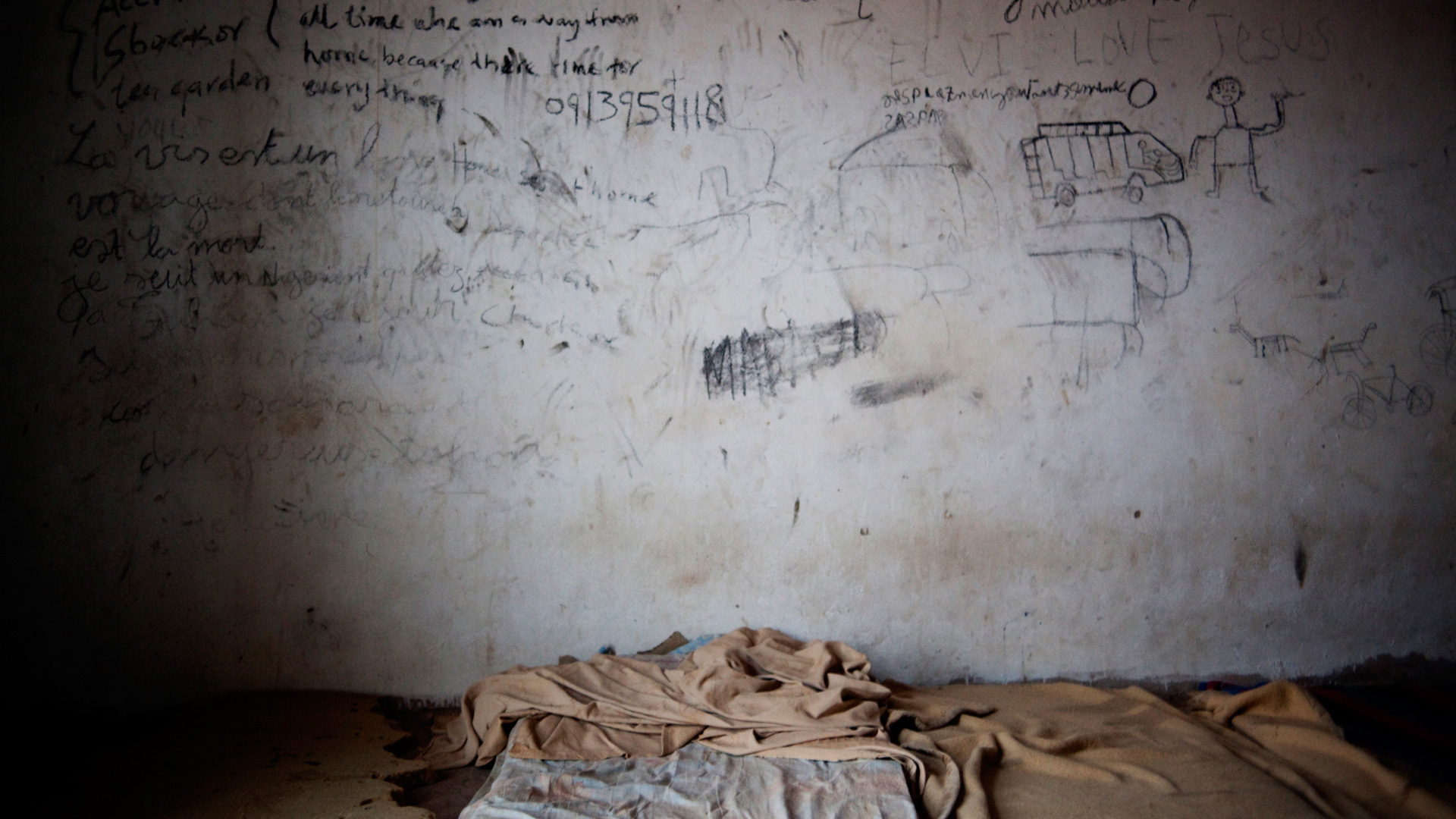

Until last year Africans picked up in the desert by Barkas militiamen – after being strictly divided by nationality – were taken to a makeshift prison until the Libyan immigration department sent them back to Niger. Now even those days are over. Mohamed Almani from the migration department in Murzuk used to organise the transportation of refugees back to Niger. He still goes in to his office, but he no longer even has enough money for phone calls, because “the banks have been closed since October”. Drawings and graffiti scratched onto the walls of the Umm al-Anarab militia’s prison show past attempts to stop the refugees; images of perilous journeys taken by young men in search of even just a minimum of prosperity. Not everyone survives the ordeal: time and again the new rulers of the Sahara come upon corpses in the desert.

The EU only cares about the refugees, not about the petrol smugglers and the illegal fishing going on before their very eyes. Seeing as we derive no benefit from illegal migration, we’re supposed to let the people go.

Issa Hassan has had enough of securing the borders of a vanished nation. He wants to marry next year. “I haven’t got the money together yet, I still need to earn more.” In his week off he shuttles back and forth between Sabha and Qatrun. A loaded Kalashnikov is stowed in the boot, as is the norm in Fezzan. Issa is interested in the daughter of a neighbouring family and exchanges text messages with her during the night shift. A marriage in Libya costs at least 40,000 dinar (15,000 euros) and the rules are strict, as with married life generally. Everyone is part of an extended family network. During the revolution young Libyans also struggled against such familial obligations.

On his taxi trips to Sabha, Issa has to stop at a number of checkpoints, where the guards will gladly turn a blind eye to earn a bit of extra money. Each undocumented refugee pays 50 dinar (15 euros). “Africans looking for work want to get to Sabha and from there head on to Tripoli. Checkpoints are lucrative, but we have sworn not to profit from the fate of migrants. That is against Islam and would be a betrayal of our friends, or my brothers – for all those who died for our freedom.”

With 50,000 inhabitants, Murzuk is one of the biggest towns in Fezzan. Ethnic tensions were already present under Gaddafi; now the Toubou are calling the shots. Before 2011, Ibrahim Saleh was the town’s chief of police. Like all Toubou, he rapidly joined the revolution – unlike the other ethnic groups, who only flew the new flag after Gaddafi’s death, he complains. Saleh is calling for more help from Tripoli, and for the reassessment and integration of tribal culture. “In the Sahara there are actually fixed social rules set by the tribes and extended families,” he explains, bent over a map of Libya. “Every car accident risks descending into a dispute between whole city districts or tribes. Traditionally, elders resolve a lot of conflicts peacefully, through negotiations. And everyone abides by their decisions.”

Two migrants from Ghana work in the building he lives in. They’re glad to have made it to the better side of the Sahara, Mohamed Agram says. Regarding the Islamist militias said to be running training camps on the Algerian border, Ibrahim Saleh prefers not to comment. “That’s a hot potato. You’d be better off asking certain people in Tripoli about it, they’re in the know,” he says.

Shahafedin Barka is more explicit: “Daesh is spreading through the tribes that were excluded from the revolution,” he warns. “And now Boko Haram is coming up from Nigeria.” He shakes his head. There are only two trafficable routes open to people smugglers, one through Madama, the other through Hisen. “Who has an interest in preventing the closure of the smuggling routes out of Niger?”

Garabulli - the epicentre of the refugee drama

Garabulli. Since the biggest maritime disaster since World War II occurred there in April 2015, with a death toll of almost 500 people, the stretch of shoreline in the eastern part of the Tajura district has come to symbolise the refugee drama in the Mediterranean. Catastrophes have been recurring here every spring since the revolt against Muammar Gaddafi. Every day unseaworthy vessels set off from among the weekend houses strewn along the shore, built by inhabitants of the capital in previous years.

Vincent Karawi from Agadez works as a gardener at a family holiday resort, which has mostly stood empty since Libya’s second civil war. “Sometimes the shore is strewn with bodies. Some boats sink after only a few hundred metres. On weekends I often don’t dare look out of my window in the morning.” As with most workers from neighbouring countries, Karawi, a Nigerien, has never considered making the crossing himself. The 22-year-old leans on his rake. “The Syrians who come to Garabulli have no choice, but many Africans simply misjudge the risk of the voyage to Europe,” he assures me.

A barter economy of all manner of commodities has long been developing in international waters off western Libya – people headed for Europe are but a small fraction of the merchandise.

Behind the high walls of the resort residences, voices can be heard. But not in Arabic: English and French dominate, spoken in a West African accent. The smugglers hide their ‘customers’ for a number of days, then they must be ready to leave at very short notice: hardly two hours pass between the order to depart and setting off. Since the beginning of 2016, more than 20,000 people from southern Libya have come to the Mediterranean coast – the exact figure is unknown. Activists from the NGO National Caucus Fezzan in Sabha estimate that before the heat wave at the start of May 2016, more than 3,000 people per week were surging into Libya’s coastal and desert cities.

Those who make it to the port city of Tripoli rent accommodation with their compatriots in Tajura, Hail Andalus or other outlying districts, and try to earn the 1,000 euros for the crossing to Europe by working odd jobs. From 5am at the major intersections of the Libyan capital, Egyptian, Sudanese and Ghanaian workers offer their services: paintbrushes, electric cables or tools indicate their skills. On average it takes six months to earn the money for the crossing, but many end up staying more than two years.

In spring, when the Mediterranean waters settle down, high season for the traffickers begins. On quiet nights up to four vessels depart from the 30km shoreline between Garabulli and Tripoli alone. NATO patrol boats can be seen on the horizon; they have replaced Lampedusa as the dinghies’ goal. Libyan naval officers in the ports of Misrata and Tripoli gaze helplessly at the vessels.

“Every time we set out in our patrol boats, we see the dinghies’ little lights,” says Abdulrahim Niwijy from the Libyan Navy, who in his bright white uniform looks a bit out of place between two rusted boats. He laments the quality of the equipment and training of his sailors – a colourful band of revolutionaries and members of the Libyan Navy whose ships had been in NATO’s crosshairs in 2011.

Tripoli under militia control

Prime Minister Fayez al-Sarraj’s Government of National Accord, in office since December 2015, has also relocated to the Abu Sitta Naval Base here. The perpetually sorrow-stricken former businessman can enter the city only rarely, because Tripoli is still controlled by militias loyal primarily to themselves. The prime minister arrived in Tripoli by boat, because the rival government, allied to Islamist groups, initiated a no-fly zone to hinder his arrival.

Officer Ashraf al-Badry looks irritably at one of the three vessels on his radar that remain fully functional. In February 2011 he protested against Gaddafi in Tripoli, and his subsequent combat mission in Sirte was rewarded with a seemingly cushy job in the navy. But unlike during the revolution, now he feels like he’s fighting a losing battle. With his finger on the radar screen, he indicates the Italian fishing boats who receive fuel from Libyan smugglers in international waters off Tripoli and Garabulli. “The EU demands that we stop the flow of migrants, but it does nothing about its own criminals.” An Italian destroyer cruises only four nautical miles from the cutter, he says with exasperation, tapping on the screen.

Seeing as we derive no benefit from illegal migration, we are supposed to let the people go.

“Cooperation would involve us protecting EU waters from people smuggling and the EU protecting us from fuel smuggling. But the EU only cares about the refugees, not about the petrol smugglers and illegal fishing going on in Libyan waters before before their very eyes. Seeing as we derive no benefit from illegal migration, we are supposed to let the people go,” al-Badry says.

Like almost every weekend, the ‘masked man’ patrol calls Mohamed Atrika to Thalil. In his childhood the 30km sand beach west of Zuwarah evoked carefree summer days. But with the revolution, the smugglers returned to Zuwarah. In February 2011, people protested here too, predominately against the forced Arabisation carried out by the Gaddafi regime in north-west Libya’s Berber regions.

Dinghies of death

There’s not much idealism left, Mohamad says. A mask covers his face. Mohamed belongs to a group of volunteers of the Red Crescent Movement, one of the last remaining humanitarian aid organisations in the country. Following battles, and on the beaches, men and woman in red overalls are called in to attend piles of bodies – refugees whose meagre sloops didn’t even make it past the first stage of the dangerous crossing. Six bodies with contorted limbs are repeatedly thrown upon the shore by the waves. The refugees had set off the night before. On this March day the men and women from the Red Crescent find a further 20 dead. A small dinghy, of the kind certified to carry 30 passengers but usually with over 100 people on board, set off and then capsized, one of the survivors reports later.

When the vessels depart in groups of six to ten, there are usually casualties, as hardly any of the passengers can swim, and the travel price of 1,000 euros mostly doesn’t include a life jacket. But the bigger the group, the easier it is for NATO patrols to find it. The smugglers assure passengers shocked at the sight of the puny vessels that the mouse-grey British and German destroyers are only 20 minutes away.

No turning back

Once on the beach, there’s mostly no turning back. Mohamed, a 26-year-old helper, over and again hears enraged screams coming from the weekend houses littered about the shoreline, which the militias rent at an exuberant price. “For three days or even longer the groups wait in the houses, until a vessel is available for the voyage or until the sea is calm. There are often only two minders, but they’re armed. In order to keep their hideout secret, they confiscate all mobile phones and refuse to let anyone return to Tripoli.” This is how a Berber explains his reserve when dealing with the militias. Two weeks earlier in Zawiyah, halfway between Zuwarah and Tripoli, nine migrants were shot dead trying to escape.

The volunteer helpers in Zuwarah also don’t speak to smugglers or refugees within hearing range of the high walls of the villas, out of fear of running into a relative. Zuwarah is a tight-knit community surrounded by Arab towns like Jumayl and Riqdalin, areas where Muammar Gaddafi mobilised counterattacks after the 2011 revolt.

Mistrust of minorities like the Berber, and the erosion of the state, are used by many as an excuse for the widespread smuggling. “If I stopped doing it, it would help IS in Sabratha,” says a well-toned man openly loading barrels of petrol into a fishing trawler at the port. While Gaddafi loyalists in the south were seeking revenge for crimes committed during the revolution, IS established itself in Sabratha, 80 kilometres east of Zuwarah. Trading state-subsidised petroleum and other goods has become the main source of income in western Libya. People smugglers and petroleum smugglers work together here. IS funnels volunteers from Tunisia over the border at Ras Ajdir to Sabratha. A barter economy in all manner of commodities has long been developing in international waters off western Libya; people headed for Europe are but a small fraction of the merchandise.

We are service providers. The Africans want to go to Europe, we don’t want them here and we offer them transit.

“We are service providers,” Ahmed Sabban says, sitting in a Turkish restaurant on the dusty main road of the coastal town of 50,000 inhabitants. “The Africans want to go to Europe, we don’t want them here and we offer them transit.” That he is sitting in a café rather than on the beach today is due to the ‘masked men’, as the local vigilante group is called. After the last major disaster in October 2015, in which more than 50 bodies washed ashore, the group decided to put a stop to the work of smugglers like Ahmed. “The main reason was actually increasing criminality, and probably also due to all the foreigners waiting at intersections all day for work,” he counters.

Ayub Sufyan’s eyes narrow when he speaks about the moment he and his friend Munir decided to take the law into their own hands. The robust 26-year-old knew that one day the smugglers’ alliance with the Islamists in neighbouring Sabratha would be a danger to Zuwarah. “We wanted to take action against any kind of anarchy, because we’d demonstrated for the sake of a constitutional state, not extremism and smugglers.”

Because many of their friends had long since lost faith and joined the smugglers, they had to work incognito, “to the extent that that is possible in a city where almost everyone is related to everyone else,” Sufyan laughs. At night they unscrewed the number plates from their cars and patrolled the beaches and intersections in balaclavas.

People-smugglers and extremists: A deadly alliance

The danger for the whole Mediterranean region that emanates from the cooperation between people smugglers and extremists can be seen in an incident from November 2015, one week before the suicide attack on the Tunisian Presidential Security forces in central Tunis. It was a quiet night, reports one of the masked men, who wishes to remain anonymous. For a long time the Zuwarahis wondered what exactly was going on in the IS training camp in Sabratha. All they knew was that the smuggler militias in Sabratha had to pay off the IS to secure access to the shoreline.

In fact, the camp south of the Roman ruins was training suicide bombers. “Late one night when I saw these two young men travelling on the only street leading to the border, I knew something was up and I stopped them,” explains a still agitated Mohamed, a mathematics student who has been with the masked squad since the beginning. He summoned his colleagues, who then found explosives and 22 mobile phones on the detained Tunisians. They were already wearing the suicide vests – during the interrogation it emerged that the 20-year-olds were on their way to Tunis. “These people will soon be sitting in boats headed for Europe,” the smugglers sitting in the café believe. They have stopped launching boats out of fear of the masked vigilante group.

We have landed seven big fish in our nets, Mohamed Talil points out cryptically. He too is hardly over 35 and rails obliquely against politics. “The elders negotiate while the young do all the dirty work.” The commander of the vigilante group proudly explains how his men stopped the boats without any assistance, or even any equipment, from NATO. He responds to the idea that the EU cooperates with the authorities in Tripoli and wants to stop the smugglers with a broad smile. “Even though we now report to the Ministry of the Interior, the public prosecutor in Tripoli is still threatening us with a lawsuit if we don’t let the smuggler bosses go.”

He fishes a document out of his pocket referring to their overstepping of their jurisdiction. When they see the document, the men around Talil curse at the top of their voices. “Maybe the Islamists in Tropoli want to get their followers back, or someone wants a relative released,” one of them says. He pulls his stocking mask fully over his head and whispers: “The EU claims that peace has returned with the Government of National Accord. But maybe a real war will break out first.”

As every morning, the Libyan Navy tugboat the Maghreb enters the port of Misrata. Whether refugees are on board or not depends on whether there is any room in the prisons. “We could bring in a thousand people every day,” the sailors say. This time there are 600 West Africans from five rubber boats. After leaving Garabulli, the men thought they had almost reached their destination: Schengen – borderless Europe. But two of the boats’ motors were faulty. Since last year the motors have been steered by refugees given a crash course by the smugglers – the navy came to the aid of the two rubber dinghies in distress. In the end almost all of the boats capsized, the captain of the Maghreb says, shaking his head. The refugees each paid 1,000 euros for the dangerous journey to Lampedusa. The Maghreb drops them off in Misrata before heading back to Tripoli. Now they are back in the civil war, back in Garabulli.

The authorities have placed 300 guest workers and refugees in a former prison for political dissidents in Garabulli, on the road to Tripoli. The government in Tripoli wants to show that they can stop the flow of people into Europe, in spite of their empty coffers. They are counting on the EU’s favour in the fight against the internationally recognised government in Tobruk. The prison lies hidden at the end of a side street lined with olive groves.

The inmates are allowed to spend one hour a day in the courtyard, while the wardens maintain their distance for fear of contracting disease. An Etritean man complains. “Look at the toilets, they stink. My wife and daughter are also here. We want to leave. There are 47 people in our cell. I have a job in Tripoli. Why won't they let us go?”

The inmates are allowed to spend one hour a day in the courtyard, while the wardens maintain their distance for fear of contracting disease.

Like everyone else, Angela Iken, a Nigerian woman, had to hand in her money and passport. “Since yesterday, when I was choked for making a complaint, I haven’t been able to eat. My husband is still working in Tripoli. The wardens told him that he could come and get me out for 1,000 dinar. When he brought the money he too was arrested and now he is doing time in Abu Salim prison.”

The inhabitants of Garabulli are unsure what will happen next. Following attacks on foreigners, ambassadors to Libya have been recalled, and deportations continue to fail due to fighting on the road to Tunisia. There seems to be no way out of Libya. Yet thanks to good wages the country has long been popular with guest workers. “We work in Libya so we can feed our families at home. A week ago we were taken from our rented house and locked up here, with no explanation,” says a Bangladeshi nurse. He sleeps on a straw mat, he says, and his sheets are full of fleas.

Perpetual power struggles

The power struggle between the two competing governments continues. Mediation efforts by the UN have been criticised, especially in eastern Libya. Militias in both parts of the country are preparing for a battle with IS in Sirte, Gaddafi’s home town. To them the migrants are merely a hindrance. More and more people smugglers set off from the city beaches every day, and occasionally a few Libyans are seen on board. The militias’ imprisonment operations haven’t altered the surge toward the Mediterranean – on the contrary.

Al-Kararim is an old school on the outskirts of Misrata. Until 2011, students from the merchant city as well as the small neighbouring town of Tawergha were taught here in eight classrooms. Since Muammar Gaddafi managed to get the dark-skinned Tawerghans, descendants of African slaves, to fight against the insurgents, dark skin has come to mean loyalty to the old regime – and following Gaddafi’s death in September 2011, Tawergha was razed to the ground.

Migrants as prisoners

Now migrants are incarcerated in al-Kararim, 1,100 in eight classrooms. For three years Mohamed Khalil’s men have tried to stop the fleeing men and women. Like al-Kararim, the other eight prisons on Libya’s Mediterranean coastline are filled to bursting point. Scabies, hepatitis and other diseases spread easily. There are barely any medical supplies.

“We have none ourselves,” Khalil says defensively. He is hardly older than his prisoners. He is adamant that reports from the Africans of beatings and torture are unfounded. Sometimes it is necessary to “punish a few criminals”, but that is not the norm. For 300 euros a month, ten former revolutionaries do shift work as wardens. A number of them are already considering taking a boat to Europe themselves – you can see the frustration on their faces. Representatives of the Sudanese embassy are the only ones who occasionally come by. People of other nationalities can’t even be deported, Khalil says.

Every day new prisoners are delivered. Some are found under tarpaulins on grocery trucks, others are arrested in their rented homes in Tripoli. “I was taken together with my brother at 2am,” says Peter Owens, an 18-year-old Nigerian. Without warning he was transferred from al-Kararim to the small prison in Garabulli. Now he is separated from his brother, and the wardens confiscated their phones. “This is hell on earth, and yet so close. In al-Kararim I could smell the sea air.”

'I have nothing there, no job, no family,' another emaciated young man from Nigeria says. 'In my country Ebola and street gangs rule.'

“Al-Kararim is too full, we have problems with the water supply and small uprisings,” is Khalil’s way of justifying the sudden transfer of prisoners. Peter shares a cell with 60 fellow unfortunates in Gaddafi’s secret police’s former prison. Once a day they’re allowed into the courtyard, which is still better than in the school, where over a hundred people are not allowed to leave the classroom allotted to them. In addition to open wounds and infections, uncertainty about the future plagues the inmates. They don’t want to return to their homelands. “I have nothing there, no job, no family,” another emaciated young man from Nigeria says. “In my country Ebola and street gangs rule.”

The wardens in the prison in Garabulli allow journalists to visit because the authorities in Tripoli want it so. The images of suffering simultaneously offer hope and serve as a warning: “Work with us, or we’ll let them all go,” the prison director laughs. There is no doubt that he has barely any concern for the fate of the Africans from eight different countries imprisoned there. “IS and General Haftar in Benghazi are my problem. These people could just move along for all I care.”

It remains unclear whether the wardens occasionally open the gates to create more room for newcomers. “I would do anything to be allowed to leave,” says one of the inmates, as visitors, after a 10-minute talk with prisoners, are asked to leave the barbed-wire compound. He has a bowl of rice in his hand. “Our daily ration,” he says. A Libyan warden gives him a severe look. You have to be careful, he warns, as some of the prisoners practise black magic. That’s why they’re no longer allowed out of their cells. “Sometimes they’ve disappeared the next morning all the same.” He gestures toward the beach with his hand, and the look on his face betrays what many Libyans openly say. In a country at war and with 400,000 internal migrants, people are happy about every boat that takes migrants to Europe.

This article first appeared in German in the 2/2016 edition of zenith Magazine. Translation by Joel Scott.